Pseudo-Riemannian manifold

In differential geometry, a pseudo-Riemannian manifold [1][2] (also called a semi-Riemannian manifold) is a generalization of a Riemannian manifold. It is one of many mathematical objects named after Bernhard Riemann. The key difference between a Riemannian manifold and a pseudo-Riemannian manifold is that on a pseudo-Riemannian manifold the metric tensor need not be positive-definite. Instead a weaker condition of nondegeneracy is imposed.

Contents |

Introduction

Manifolds

In differential geometry, a differentiable manifold is a space which is locally similar to a Euclidean space. In an n-dimensional Euclidean space any point can be specified by n real numbers. These are called the coordinates of the point.

An n-dimensional differentiable manifold is a generalisation of n-dimensional Euclidean space. In a manifold it may only be possible to define coordinates locally. This is achieved by defining coordinate patches: subsets of the manifold which can be mapped into n-dimensional Euclidean space.

See Manifold, differentiable manifold, coordinate patch for more details.

Tangent spaces and metric tensors

Associated with each point  in an

in an  -dimensional differentiable manifold

-dimensional differentiable manifold  is a tangent space (denoted

is a tangent space (denoted  ). This is an

). This is an  -dimensional vector space whose elements can be thought of as equivalence classes of curves passing through the point

-dimensional vector space whose elements can be thought of as equivalence classes of curves passing through the point  .

.

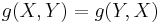

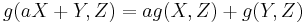

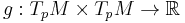

A metric tensor is a non-degenerate, smooth, symmetric, bilinear map which assigns a real number to pairs of tangent vectors at each tangent space of the manifold. Denoting the metric tensor by  we can express this as

we can express this as

.

.

The map is symmetric and bilinear so if  are tangent vectors at a point

are tangent vectors at a point  to the manifold

to the manifold  then we have

then we have

for any real number  .

.

That  is non-degenerate means there are no non-zero

is non-degenerate means there are no non-zero

such that

such that  for all

for all  .

.

Metric signatures

For an n-dimensional manifold the metric tensor (in a fixed coordinate system) has n eigenvalues. If the metric is non-degenerate then none of these eigenvalues are zero. The signature of the metric denotes the number of positive and negative eigenvalues, this quantity is independent of the chosen coordinate system by Sylvester's rigidity theorem and locally non-decreasing. If the metric has p positive eigenvalues and q negative eigenvalues then the metric signature is (p, q). For a non-degenerate metric  .

.

Definition

A pseudo-Riemannian manifold  is a differentiable manifold

is a differentiable manifold  equipped with a non-degenerate, smooth, symmetric metric tensor

equipped with a non-degenerate, smooth, symmetric metric tensor  which, unlike a Riemannian metric, need not be positive-definite, but must be non-degenerate. Such a metric is called a pseudo-Riemannian metric and its values can be positive, negative or zero.

which, unlike a Riemannian metric, need not be positive-definite, but must be non-degenerate. Such a metric is called a pseudo-Riemannian metric and its values can be positive, negative or zero.

The signature of a pseudo-Riemannian metric is (p, q) where both p and q are non-negative.

Lorentzian manifold

A Lorentzian manifold is an important special case of a pseudo-Riemannian manifold in which the signature of the metric is (1, n−1) (or sometimes (n−1, 1), see sign convention). Such metrics are called Lorentzian metrics. They are named after the physicist Hendrik Lorentz.

Applications in physics

After Riemannian manifolds, Lorentzian manifolds form the most important subclass of pseudo-Riemannian manifolds. They are important because of their physical applications to the theory of general relativity.

A principal assumption of general relativity is that spacetime can be modeled as a 4-dimensional Lorentzian manifold of signature (3, 1) or, equivalently, (1, 3). Unlike Riemannian manifolds with positive-definite metrics, a signature of (p, 1) or (1, q) allows tangent vectors to be classified into timelike, null or spacelike (see Causal structure).

Properties of pseudo-Riemannian manifolds

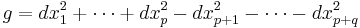

Just as Euclidean space  can be thought of as the model Riemannian manifold, Minkowski space

can be thought of as the model Riemannian manifold, Minkowski space  with the flat Minkowski metric is the model Lorentzian manifold. Likewise, the model space for a pseudo-Riemannian manifold of signature (p, q) is

with the flat Minkowski metric is the model Lorentzian manifold. Likewise, the model space for a pseudo-Riemannian manifold of signature (p, q) is  with the metric

with the metric

Some basic theorems of Riemannian geometry can be generalized to the pseudo-Riemannian case. In particular, the fundamental theorem of Riemannian geometry is true of pseudo-Riemannian manifolds as well. This allows one to speak of the Levi-Civita connection on a pseudo-Riemannian manifold along with the associated curvature tensor. On the other hand, there are many theorems in Riemannian geometry which do not hold in the generalized case. For example, it is not true that every smooth manifold admits a pseudo-Riemannian metric of a given signature; there are certain topological obstructions. Furthermore, a submanifold does not always inherit the structure of a pseudo-Riemannian manifold; for example, the metric tensor become zero on any light-like curve.

See also

- Spacetime

- Hyperbolic partial differential equation

- Causality conditions

- Globally hyperbolic manifold

Notes

References

- Benn, I.M.; Tucker, R.W. (1987), An introduction to Spinors and Geometry with Applications in Physics (First published 1987 ed.), Adam Hilger, ISBN 0-85274-169-3

- Bishop, R.L.; Goldberg, S.I. (1968), Tensor Analysis on Manifolds (First Dover 1980 ed.), The Macmillan Company, ISBN 0-486-64039-6

- G. Vrănceanu & R. Roşca (1976) Introduction to Relativity and Pseudo-Riemannian Geometry, Bucarest: Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România.